Value added processing

Value addition is the transformation of a raw commodity or commodities into a processed product through the use of raw materials, labour, time and technology, all blended in a way that ensures increased economic return. Value added processing almost always increases shelf life, and it can therefore be used to preserve perishable surplus product.

In the context of reducing waste and increasing efficiency, it is a useful tool to derive value from product that cannot be sold onto the fresh produce market for certain reasons, such as:

- Does not meet size specification

- Does not meet certain cosmetic standards but is perfectly edible

- Will be over ripe by the time it reaches the fresh produce market

- Is underripe but can be used in processed product (e.g. green tomato chutney)

This guide therefore assumes that the volumes being processed are relatively small, and while processing is important, it is not the core activity of the business. It therefore focuses on low cost/ low volume systems.

This guide is intended to be very a brief overview of the main types of processing that could be appropriate for small businesses, and an outline of the key food safety legislation they would have to comply with. In Wales, we are fortunate to have a network of organisations and a number of projects dedicated to supporting food businesses, details of which are provided in the ‘support and further information’ section. If you are considering value added processing it is recommended that you contact them.

Types of value-added processing

There are number of processes appropriate for fruit and vegetables. Some, such as irradiation, require expensive specialist equipment/ facilities and are therefore not widely used by growers in Wales, but many other processes are useful to the small – medium scale grower. These include:

| · Canning/ Bottling | · Pickling |

| · Dehydration | · Lacto fermentation |

| · Pasteurisation | · Jam/ Chutney making |

Canning/ bottling

Canning, or bottling, involves cooking food in sealable containers to sterilise it and deactivate enzymes than can lead to spoilage. Traditionally, containers have been made of metal but any sealable container can be used. During heating the air is driven from the can or jar. As it cools a vacuum seal is formed which prevents air from getting back into the product and therefore re-contamination of the food. This presentation includes more details.

The main concern is contamination with Clostridium botulinum, the spores of which produce a deadly toxin. Acid conditions (pH of 4.6 or lower) kill the bacteria. The type of canning depends therefore on the acidity of your product so ALWAYS measure the pH to ensure the right method is used. Where appropriate, the addition of an acid such as vinegar can bring the pH down to a safe level

Boiling water and steam methods are safe for some horticultural products routinely canned, including tomatoes (although some varieties are bred to be less acidic), pickles jams, jellies and other fruit preserves. Jars of food are heated in a water bath or steam cabinet while completely covered with boiling water or steam for at least 10 minutes. For all foods with a pH above 4.6, you must use pressure canning, which essentially involves using a scaled up pressure cooker.

The length of time required depends on which kind of food is being canned. The boiling point of water reduces with altitude, so treatment times also depend on your elevation. The appendices of this guide give details.

Pasteurisation

Pasteurization is similar to canning, but the product is not completely sterilised. The food, almost always a liquid such as fruit juices or passatas, is heated to a specified temperature and held there for a period of time depending on the product. This is enough to kill some, but not all, bacteria and to disable certain enzymes that catalyse deterioration processes. This means the shelf life is extended significantly but not indefinitely. The advantage of pasteurisation over canning it that the taste and texture is less affected by the former. There are various approaches

- Batch pasteurisation is the simplest and approach and involves heating to 63oC for about 30 minutes. This can be done in a vat, or by placing bottles/ containers of the ‘raw’ product in a water bath. This method is most suitable for many small-scale businesses.

- Ultra High Temperature (UHT) pasteurisation delivers a short, very intense burst of heat which brings the juice up to about 120oC but only for a fraction of a second. This is widely used in larger scale operations, but it can alter the taste of the product

- High Temperature Short Time (HTST) pasteurization is somewhere between batch and UHT. The product is held at 77 oC for a minute or so and then rapidly cooled to 7 o It is possible to vary these (lower temperatures can be compensated for by long periods). This favoured by larger scale operations as it can be done as a continuous flow rather than in batches and does not affect the taste/ quality as much as UHT

UHT and HTST pasteurization require specialist equipment and relatively high investment.

Case Study: Pasteurising Apple juice at Ty’n yr Helyg

Inspired by a workshop led by Chris Creed of ADAS and a follow-up training course at Food Centre Wales, Horeb, a small group started apple pressing for juice using an elderly press that the Herefordshire apple grower Ian Pardoe had found for Ty’n yr Helyg growers, David and Barbara Frost, years earlier.

By the end of the group’s second year they decided it was time to upgrade and they invested in a 40-litre rack and cloth press. Then followed the acquisition of an electric mill to scrat (or mill) the fruit.

The yield of juice at pressing depends on the variety of apple used and the rootstock it’s grown on. A guide ratio is to gain 1 litre of juice from every 2.5 kg of apples. At Ty’n yr Helyg, the best yield achieved has been a ratio of 1 litre per 1.8 kg of apples from a blend of Discovery and Bramley varieties.

All the juice is pasteurized. David Frost says, “Apple juice may taste great straight from the press, but in order to store juice and to avoid problems such as Patulin[1], pasteurization is essential. Using the pasteurizer we hold juice in 75cl glass bottles (or plastic bags for boxed juice) at 75 degrees C for 25 minutes. The longer the pasteurizing period, the longer the juice can be stored but then there is also an associated loss of flavour. Our method means that the juice keeps for up to 12 months and retains its best flavour.”

Research[2] shows that when fruit is processed into juice and bottled on the farm, it can be a valuable way of maintaining farm income. For many growers with apple trees, juice is a low-cost enterprise to set up but production can be labour intensive. Best returns will come from on-farm tourism, direct sales at market stalls and box scheme sales.

More details here

Scratted Apples Scratted Apples |

Rack and cloth press Rack and cloth press |

Pasteurizing juice Pasteurizing juice |

|

Dehydration

Dehydration is one of the oldest and in many ways the simplest methods of food preservation. The moisture content is reduced to a level below which microorganisms cannot survive, usually between 10 -15%. Compared to other preservation methods in Wales it is less widely used, but is useful for some products such as apples and mushrooms.

The simplest is oven drying it is suitable only for small quantities on an irregular basis because: it is inefficient in terms of energy use; it is difficult to maintain a low drying temperature in an oven; foods are usually darker, more brittle and less flavourful than foods dried by a dehydrator.

Electric dehydrators are much more energy efficient and deliver a better quality product than other methods. They are fundamentally simple in design, comprising of a heat source, a ventilation system, and racks on to which food is placed. They vary in price and sophistication, but are usually worth the investment in terms of reduced energy consumptions and consistency of the product

This guide has further details

There are other methods of dehydration such as freeze drying and microwave based systems, but these are characteristic of larger scale, specialist processing operations, and are unlikely to be applicable to producers wishing to preserve surplus fresh vegetables

Pickling

The preservative ingredients in pickling are salt combined with acid such as the acetic acid in vinegar. It is possible to preserve a wide range of vegetable in this way, but the most common examples include:

- Brined pickles, usually specific varieties of cucumbers specially grown for this purpose, although a traditional recipe for conventional varieties could be scaled up

- Fresh pack or quick process pickling involves boiling in hot vinegar, spices and seasonings (sometimes the product is cured in brine as above beforehand).

- Whole of sliced fruit pickles cooked in a sweet-sour syrup, often using lemon juice or cider vinegar to reduce the pH

- Fruit and vegetable chutneys, using chopped fruits cooking in vinegar usually with a quantity of sugar to sweeten the taste and augment the preservative action of vinegar

Lactco Fermentation

This is another acid-based preservation method and used to produce products such as sauerkraut or Kimchi. It relies on salt-tolerant Lactobacillus to anaerobically convert the sugars present in fruit or vegetables into lactic acid. This reduces the pH to 4 – 4.5, at which point the organisms responsible for deterioration are unable to survive. This gives the product a shelf life of up to 6 months. Initially the product can be submerged in brine or crystalline salt can be simply added to the raw product. It is then placed in fermenting vessels, with an air lock that allows the carbon dioxide out, but prevents oxygen getting in which allow aerobic organisms to thrive and lead to spoilage.

Case study: Parc y Dderwen

Parc y Dderwen, run by Lauren Simpson and Phil Moore, produces fermented vegetable products. They recently had their application for a One Planet development near Clynderwen approved, and by next year will be growing all their own produce and using their own on site commercial kitchen, In the meantime production is based at the Community Kitchen in Hermon, Carmarthenshire, where they produce about 200 Kg/ Month. At present the main products are Sauerkraut and Kimchi, but they have plans to expand their range to include pickles and ketchups.

Cabbages and other vegetable ingredients (such as carrots, chillies) are sliced by machines and chopped cabbage is layered with salt to create optimal conditions for the Lactobacillus. The salt and the cabbage are then vigorously mixed together for about 15 minutes which helps to release the water contained within the plant tissues. It is then transferred to plastic tubs with an airlock. The tubs are then stored at ambient temperature for 3 – 4 weeks. After this time, it is tested to make sure the pH is about 4 (and if not left for longer). It is then transferred to jars. A sample from each batch is sent for microbial testing to make sure it is safe and that the pH is low enough, after which the jars are dispatched to retailers (independent shops throughout South West Wales).

Lauren said ‘Fermenting foods could be an excellent way of adding value to produce that for one reason or another doesn’t make it on to the conventional market. The production process is very simple and it’s relatively inexpensive to set up. There is a cost attached to the bacterial testing, so it makes economic sense to test reasonably large batches; we make a 100Kg batches every two weeks. The biggest barrier for many producers is a lack of confidence. However, once we started we realised that as long as you adhere to simple rules around food safety, it is really quite simple, and does not require a huge amount of investment.’

Slicing cabbage Slicing cabbage |

Mixing in salt and other ingredients Mixing in salt and other ingredients |

Fermenting tubs (air lock to be added) Fermenting tubs (air lock to be added) |

Finished product Finished product |

Jams, jellies and chutneys

Jams and chutneys rely mostly on the preservative action of sugar. In high concentrations, sugar draws water out of the cells of micro-organisms through a process called osmosis. Without sufficient water, the bacteria can’t grow or divide. There are several steps:

- The fruit/ vegetables are washed and prepared, depending on the product: Soft fruits can be blended and strained; apples are peeled, cored, sliced and diced; Cherries may be soaked and then pitted before being crushed.

- They are then pasteurised (see above)

- For jellies, the pulp is forced through a sieve to remove seeds and skin

- Pre-measured quantities of fruit and/or juice, sugar, and pectin are blended in cooking kettles and boiled. The mixtures are usually cooked and cooled several times

- Any additional flavourings are added

- The mixture place in jars and cooled

Case study: Fynnon Beuno

Fynnon Beuno, run by Jane Marsh, produces jams and cordials from raspberries, strawberries, plums & damsons and blueberries grown on their smallholding near St Asaph. They also produce a range of chutneys as a way of dealing with gluts. Produce is sold through an on-farm café/ teashop and through local outlets.

For jams (see Certo for detailed recipes), the freshly harvested fruit is washed, packed into 1 kg bags and frozen to be processed in the winter months when they are less busy in the field. The jam making process is simple. The fruit is placed in maslin pan with an equal weight of sugar. The mixture is brought to a rapid boil for about 90 seconds, after which pectin is added (which reduces the time needed for boiling). The jam is left to cool slightly and placed in sterilised jars. The jars are then stood in a boiling water bath for 10 minutes (as outlined in the ‘canning’ section above) and left to cool overnight.

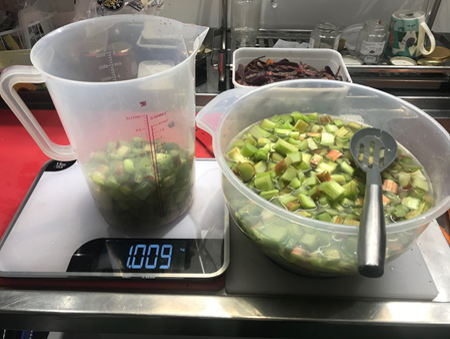

Chutneys require more preparation time. All the raw ingredients (usually apples, onions, beetroots and swedes) have to be peeled, washed and cubed. Once ready, they are placed in in a pan with muscovado sugar and vinegar (the proportions are important but vary according to the amount of sugar vegetables and whether sultanas ae added to the mix). They are cooked, with a spice ball added for flavour, for about 90 minutes, until the mixture has reduced down. They are then placed in sterilised jars and transferred to a boiling water bath as described for jam.

Jane started the business in November 2018 from the farmhouse kitchen, but quickly decided she needed the facilities a commercial kitchen offered. ‘It was a significant investment’ she said. ‘It cost us about £7,000 to upgrade, but we managed to keep the costs down by buying good second equipment. Efficiency and minimising waste is very important to us. For example, we ferment the apples skins and cores from the chutney making process to make cider vinegar which we use in our chutneys and sell any surplus. All our organic waste is composted, and the nutrients returned to land to support the next crop of fruit and vegetables.’ More information

|

Weighing out |

Ingredient mixing |

Rapid boiling Rapid boiling |

|

Food safety and hygiene

The production, processing, distribution and retail of food in Wales and the UK is governed by strict legislation to help ensure that food is safe to eat. Food legislation is overseen by the Food Standards Agency and usually implemented on the ground by local authorities through Environmental Health Officers. Details of your local food safety team are available here: All food businesses are subject to regular inspections. Based on those inspections, every business is given a ‘Food Hygiene Rating’ which, if you are selling to the public you must display on your premises.

It is absolutely essential that you fully understand your responsibilities and commitments. In Wales there is a network of Centres dedicated to supporting Welsh food businesses, who will help and support you in all aspects of food processing, including courses on food safety and hygiene (see contacts and resources form further information)

In general terms responsibilities include:

- Ensuring food is safe to eat

- Keeping records to demonstrate traceability

- Withdrawing unsafe food and complete an incident report

- Only use approved additives at or below maximum permitted level.

Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) plans

The HACCP is central to achieving and maintaining food hygiene and safety standards. In outline it:

- Identifies any hazards that must be avoided, removed or reduced

- Identifies the critical control points (CCPs) – the points when you need to prevent, remove or reduce a hazard in your work process

- Sets limits for the CCPs and ensures they are monitored adequately

- Shows how things will be put right if there is a problem with a CCP

- Puts checks in place to make sure your plan is working

- Keep records

Given the importance of the drawing up and implementation of the plan, accessing advice and training is highly recommended (see ‘Support and Further information’)

Premises

Premises used for food preparation must meet minimum standards including:

- Handwashing facilities

- Floors, walls and ceilings must be: maintained in a good condition; easy to clean; disinfected; smooth; hard-wearing; washable; free from condensation, mould and flaking paint or plaster

- Windows and doors must be constructed in a way that prevents dirt from building up

- Surfaces (including surfaces of equipment) must be maintained in a good condition, easy to clean and disinfected

- Separate sinks must be provided, where necessary, for washing food and cleaning equipment in food preparation areas

- Every sink must have an adequate supply of hot and cold water for washing food and be of drinking quality. These facilities must be kept clean and be disinfected

- All items, fittings and equipment that food touches must be kept in good order, repair and condition; cleaned effectively and be disinfected frequently enough to avoid any risk of contamination

- You must have adequate facilities for storing and disposing of food. You must remove food waste, and other rubbish, from rooms containing food as quickly as possible to avoid it building up and attracting pests.

Support and further information

Support and training

- Food Centre Wales, Horeb, West Wales: gen@foodcentrewales.org.uk

01559 362230, foodcentrewales.org.uk - Food Technology Centre, Coleg Menai, North Wales: ftc@gllm.ac.uk; 01248 383345; foodtech-llangefni.co.uk

- ZERO2FIVE Food Industry Centre, Cardiff Metropolitan University: ZERO2FIVE@cardiffmet.ac.uk; 02920 416306; zero2five.org.uk

- Project Helix http://foodinnovation.wales/project-helix-1/

- Food Skills Cymru https://www.foodskills.cymru/

Value added processing

- Canning ISEKI-Food Association

http://sustainablefarming.co.uk/susfarming/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Food-Canning.pdf

- Drying Fruit for Storing, Grow veg

https://www.growveg.co.uk/guides/drying-fruit-for-storing/

- Preservation of fruit and vegetables: Agrodok-series No. 3 (2003). Agromisa Foundation, Wageningen, https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/52981/1162_PDF-1.pdf?sequence=1

- Small-scale apple juice production The Organic Grower

http://sustainablefarming.co.uk/susfarming/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/OG41_juice_Frost.pdf

Food safety and hygiene legislation

- Food Standards Agency https://www.food.gov.uk/

- Local Council enforcement officers https://www.food.gov.uk/contact/consumers/find-details/contact-a-local-food-safety-team

- General responsibilities: https://www.gov.uk/food-safety-your-responsibilities

- Choosing the right premises

https://www.food.gov.uk/business-guidance/setting-up-a-food-business

- HACCP Principles https://www.gov.uk/food-safety-hazard-analysis

[1] Patulin is a toxic fungal metabolite which occurs in apples that have been spoiled by mould growth. It is a significant problem in apples and apple products, especially apple juice. Its effects are toxic and but it’s not usually found in alcoholic drinks such as cider. http://www.foodsafetywatch.org/factsheets/patulin/

[2] HDRA (2005) Economics of Organic Top Fruit Production. Report to Defra OF0305

Jarring

Jarring